The Coronaspiracy Part 2: The Pasteur Conspiracy

On the Origins of The Germ Inversion.

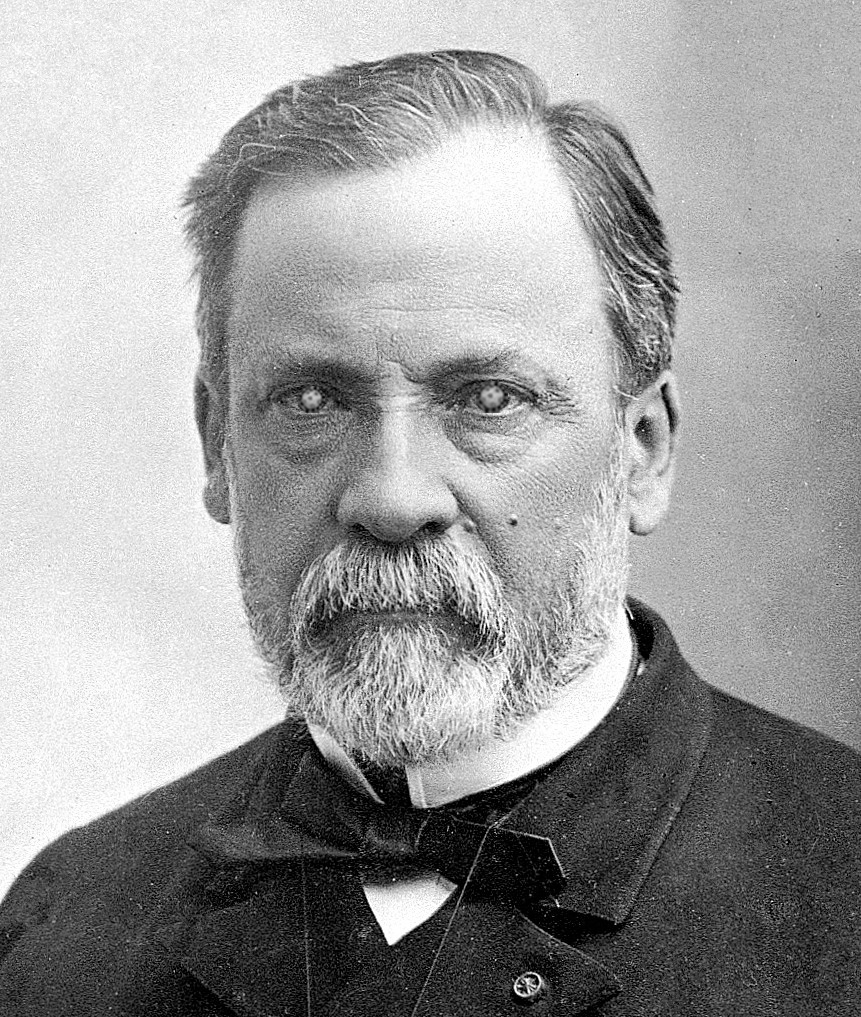

You have almost certainly heard of Louis Pasteur, given he is widely credited with outlining the central tenets of the Germ Theory of Disease as it is understood and applied today (not to mention the damage his name has done to the cause of raw cow juice).

But have you also heard of Antoine Béchamp? Well yes, if you are a true ‘Rona dissident you almost certainly have by now: he is the generally agreed upon Terrain OG, after all; the instigator of concepts such as the Microzymas and Pleomorphism that the Germ Conspiracists would prefer you not to know much about; the French RFK Jnr (Tom Cowan?) to Pasteur’s modern day Fauci, even.

France vs the Germ(ans)

For those not up to speed with the basics: Pasteur and Béchamp were contemporaries and adversaries, both highly prominent in the late 1800s French intellectual scene. Fresh off a humiliating defeat to Germany (not the last lol) — lacking both pride and land — the French decided to focus on what they do best: smug intellectual superiority with a side dose of cultural inversion. Significant investment was made into universities — funded by the Church of Rome, hooray — in the hope of producing a generation of world leading elite thinkers to see what long held belief systems they could uproot. And, by golly, did Louis not disappoint.

The fact that this post-war regroup by the French birthed what I call The Germ Inversion — the gradual transformation of the Germ Archetype from the initiator of life into its greatest threat — is a delicious irony… and a really weird shadow projection revenge flex. Basically: having been owned on the real battlefield, the French (whether consciously or subconsciously) shifted their warfare against the Germs to the biological arena.

If you do a simple internet search of Pasteur vs Béchamp, you will come across a range of articles comparing their competing theories, including more than a few that are highly critical of Pasteur — not just for his ideas, but for his scientific ethics and overall character (shit bloke, basically).

Such criticism has not just popped up in our After Delta era, where the lid of the terrain theorist box has well and truly been blown off. This is a Before Covid debate that has been raging for over a century; two books, one published in 1923 (Béchamp or Pasteur? A Lost Chapter in the History of Biology by Ethel Hume) and another in 1942 (Pasteur: Plagiarist, Imposter by R. B. Pearson) are lengthy and impressively savage smear jobs against Pasteur’s life and works. In fact, these two books — in particular Hume’s formidable effort, which we (me) will be focusing on — both charge that it was Béchamp who was the true genius, the more accomplished scientist, and — most importantly (hopefully) — the better human being.

Of course, as far as our esteemed and not at all ideologically and morally compromised medical establishment is concerned, there is no debate at all: Pasteur and Germ Theory have been conclusively proven correct over centuries of real world examples (muh Polio), while Béchamp — who it may gracefully be conceded was without doubt a competent scientist and decent enough chap — faded into obscurity due to his increasing anti-Jibby Jab ramblings.

Truly, there is nothing new under our local sun.

So, what is The Pasteur Conspiracy? What use is there in continuing to rehash this historical showdown between two croissant-guzzling intellectual heavyweights, when so much has already been said?

Well, mainly, because I have already committed to it. The intention of The Coronaspiracy is to take a holistic conspiratorial lens to the Plandemic: to place this shitshow into its proper malevolent context, while enjoying and appreciating it as the climax to the greatest Apocalyptic Virus Porn (AVP) movie ever made.

To do this script justice, we need an origin story. No, not Wuhan: let’s save that for The Bioweapon Conspiracy (assuming I don’t lose interest after this instalment). Like any good AVP thriller, we have to begin with a flashback — by going back in time, Bruce Willis in 12 Monkeys-esque, to when our plot was first born.

So if we are going to do it, let’s keep it spicy.

An interesting little prelude, before we get to the main actors.

Around two decades before Louis was even on the scene, another famous medical icon — Florence Nightingale no less, the OG Nurse — was challenging (to put it mildly) the very understanding of disease that lies at the heart of not just Germ Theory but our whole health system:

“The specific disease doctrine is the grand refuge of weak, uncultured, unstable minds, such as now rule in the medical profession. There are no specific diseases; there are specific disease conditions.”

While inevitably adopting the basic tenets of Germ Theory (albeit with some criticism, bless), it is interesting to look at Nightingale’s theories and early writings now, to see that there was little importance given to germs in her model for nursing diseased people back to health.

It was this accepted medical paradigm that Pasteur — with the help of his elite chums — uprooted and replaced with his own. This was primarily thanks to his celebrated work on silkworms — work, as Hume lays out in fairly undeniable detail in her 1924 book, he shamelessly piggy-backed off Béchamp’s laboratory findings.

Hume has no shortage of free character assessments of Pasteur, which we will return to shortly. However, for the sake of balance, it is not just this unashamedly un-objective, century-old character assassination that we have to create a contrasting picture of The Real Pasteur.

One of the biggest red flags of Pasteur’s legacy was his reluctance to release his laboratory notes for scrutiny — it was only after the death of his Grandson in 1975 that they were finally made available. The most comprehensive analysis of these notes was undertaken by the renowned science historian Gerald Geison, who released his findings in the book “The Private Science of Louis Pasteur”.

The book makes a fairly sharp assessment of the skill set that was most crucial in Pasteur’s theories becoming widely accepted:

“Although experimental ingenuity served Pasteur well, he also owed much of his success to the polemical virtuosity and political savvy that won him unprecedented financial support from the French state during the late nineteenth century.”

Such comparatively gentle criticism of Pasteur’s legacy — and the mild academic controversy that followed — was still too much for some butthurt acolytes, who quickly came to his defence.

But what is notable about this mainstream-approved re-assessment of his character was what is omitted: a thorough interrogation of the scientific validity of the theories that he is still most widely known for, along with his battles with Béchamp. Poor Antoine, in fact, barely cracks a mention in Geison’s work.

Pasteur’s main controversies were said to be after his theories had been soundly established, when he moved into the field of (of course) Jibby Jab development — most notably the allegation that he engaged in academic mispractice during the discovery and promotion of his Anthrax and Rabies injections. This book review from 1995 (from the New York Times, no less) does not pull any punches in this regard:

“Pasteur is not attractive: aloof, gruff, authoritarian, secretive, competitive, a ruthless opponent. That, from the point of view of his science, is irrelevant. His misconduct about anthrax and rabies is much more reprehensible…”

Yet, ultimately, this is as far as we are allowed to question one of the defining characters of our modern scientific age. Cue the cope:

“Mr. Geison has gone some way to deconstruct the myth of Pasteur and the belief that all of his science is pure and beautiful, but most of Pasteur's beautiful science still shines brightly. Dishonesty is the antithesis of the scientific endeavor; yet we can be grateful to Pasteur in spite of his misdemeanors.”

Published in Alex Berenson’s spiritual home, we should not be surprised to encounter such a sublime artefact of Germ Conspiracist Gatekeeping.

The Deathbed Confession

Before we go any further, we must deal with the elephant in the terrain: the infamous Deathbed Confession.

The popular re-telling of this event is that Pasteur recanted and acknowledged Béchamp’s theories to be correct as his final act on this Demiurge-inflicted prison planet. Obviously too petty to give full credit, the quote was apparently directed towards fellow early Germ-dissident Claude Bernard:

“Bernard was right: the pathogen is nothing; the terrain is everything”.

But (and this is not a popular question I know): did he really?

What exact primary evidence do we have for this event occurring, aside from secondary re-tellings passed on in an endless game of terrain-theorist-whispers? Perhaps tellingly, despite all the criticism of Pasteur, the alleged recant is not contained in Hume’s aforementioned weighty and intimidating tome (I made it roughly a third of the way through, enough to feel qualified enough to give you my hot takes).

The truth, as far as I can determine, is that we have no such evidence: we may never be able to prove or disprove whether Pasteur did indeed recant his life’s work in his last act on/in this mortal coil.

Not that that should stop us: as has been well established by my more disciplined and scientifically-minded terrain comrades, there is also no evidence to support the existence of contagious pathogenic biological entities — yet that hasn’t stopped an entire Medical/Political/Archonic belief system being created in their honour.

Thus, while the Deathbed Confession could well be fiction, such a recant would be a fitting last act by a shameless opportunist seeking to escape some of his accumulated hefty karma before he embarked on what I would presume was a fairly brutal life review with his spiritual overseers — quite possibly before agreeing to reincarnate as Tony Fauci so he could finish the job.

In other words: you have my permission to keep running with it.

Spontaneous Generation and Fermentation

So: what further slander and accusations can we hurl at old mate Louis?

Before we dig deeper into the dirt buried in Hume’s book — and there are indeed more beans to be spilled — it must be acknowledged that the scientific language employed is often daunting in its detail.

These are not small ideas being tested and debated — fiercely, as the French are prone to do — but are as fundamental to the workings of the natural world as one can hope to explore: what is living matter, how does it come into being, and what is the catalyst for its transformation? In fact, after working my way as far as I could stomach, I was left with one inescapable conclusion: they don’t do science like this anymore.

Nonetheless, we do our best. The necessary theoretical context for The Pasteur Conspiracy revolves around two concepts, and it is through these two concepts that we can gain insight into the minds of each man.

The first is “Spontaneous Generation”: the theory that living matter came (and continues to come) into being from some hypothetical formless medium through a spontaneous and largely unexplainable process. It is to Germs what The Big Bang is to Space: a placeholder origin story that essentially serves to distract from the fact that they clearly don’t understand the thing they are trying to explain to us. As Hume succinctly summarises:

“Imagination played more part in such a theory than deduction from tangible evidence”.

Sounds like NASA. The second concept is “Fermentation”, well-known as the chemical process through which alcohol is produced.

Pasteur is historically accepted as both the disprover of spontaneous generation and the pioneer behind the elucidation of the fermentation process. However, Hume argues that his original findings — made in August 1857 — were simply a basic bitch continuation of spontaneous generation: confirming, through his cutting edge use of microscopy, that the process was driven by the secretions of minute “lactic yeast” organisms, but offering no new ideas about the “where” and “why”.

Essentially: Pasteur lacked the scientific capacity and/or curiosity to uncover the specific biological mechanism that initiates the fermentation process, and the broader biological purpose that it served — something he readily admitted to 3 years later:

“Now in what does this chemical act of decomposition, of the alteration of sugar consist? What is its cause? I confess that I am entirely ignorant of it”.

The Beacon Experiment

If a fundamental inclination towards ignorance over curiosity is one of the hallmarks of Pasteur’s legacy, then so too is plagiarism. Because what we also learn is that the hard work behind Pasteur’s much celebrated work on fermentation had been already undertaken by Béchamp: most notably in his famous “Beacon Experiment” in 1854.

Again: this is not easy material for our dumbed down scientific minds to digest (including mine), but these are the basics.

These experiments were designed to test the nature of fermentation that would occur in a solution of cane sugar and distilled water, held within a stoppered container. This was to be compared to control samples containing varying amounts of zinc chloride and calcium chloride. Resultant moulds were found only in the pure sample, showing a preventative function of the salts. Béchamp continued his experiments across 1856 and 1857, this time with a greater variety of chemical compounds added to the sugar solution (creosote was found to be particularly effective as an added preventative agent).

The key finding of these experiments was that it was the presence of elementary living organisms that caused fermentation, rather than it being a natural “spontaneous” action of the water. It was, Béchamp would ultimately conclude, not just a random and unexplainable process (as Pasteur was initially content to conclude) but an intelligent and directed process undertaken by creative biological entities.

It was this foundation upon which Béchamp would develop into his theory of the “Microzymas”: tiny granular entities that exist inside every living organism. These entities represent the basic building blocks of life, while also serving a vital regulatory function in their ability to break down unwanted organic material — including dead, dying or diseased cells.

Pasteur went the other route: looking outward — as those who see themselves as separate from nature tend to do — pointing the finger at airborne germs, and the rest is pretty much history.

Wait… so it all boils down to Going Within? Truly, there is nothing new under our local holographic sun and moon.

The Spiritual War for Science

Why do we not hear more about these shape-shifting Microzymas — later described as Somatids by Gaston Naessans — being the biological missing link that they are?

Perhaps it is because, without the endogenous salutogenic germ, the gap can be filled by invading exogenous pathogenic germs that the Germ Conspiracists have used to convince us to create barriers within society in order to be protected from.

Through the concepts of spontaneous generation and fermentation, we don’t just see two clear examples of Pasteur being at best a greasy pole climber and at worst an outright fraud — we see the normalisation and celebration of an incurious and hubristic approach to understanding the natural world.

At its heart, The Pasteur Conspiracy points to something quite profound: a clash of fundamental scientific worldviews, which Hume rather provocatively reduces down to materialism versus creationism. I’ll go one better and call it the spiritual war for the soul of science. Is it simply enough to prove that there is a process by which organic life is formed — or, should we be seeking to understand the specific, life-affirming reason why nature initiates this process?

Our modern day Pasteur acolytes are not uniformly characterised by ill-intent (although that is of course entirely probable at the higher levels), but by practicing lazy science.

It is the mindset that thinks it is ok to come up with a test that shut the world down — even though, by their own admission, they didn’t have the actual virus when they designed the test. All G, says the CDC: we have most of it stored away somewhere from the original 2003 SARS, the computers will tell us the rest!

But: it is also the mindset that thinks it is reasonable for an artefact produced from contaminated and poisoned tissue in a test tube to exceed the burden of proof for isolating a contagious pathogenic virus.

If we stop short, if close enough is good enough — if we are content with confirming rather than challenging — then we allow for projection, bias and belief to take over. In an outward looking biophobic world, where fear of an invading nature is a constant fixture, the result is inevitable.

Whether consciously or subconsciously, it was this worldview that was projected on to the natural world by Pasteur — and is still being projected to this day, both consciously by our Germ Conspiring Conspiracists and subconsciously by those still perpetuating Germ Theory’s central tenets.

In spicier words: Pasteur’s was the original Germ Inversion, and we are seeing the final fruits of that satanic seed today.

Basically: Fuck Louis. Let’s finish by giving due respect to the real dude.

What both of our anti-Pasteur tomes make clear is that Béchamp was the better scientist, certainly in a technical sense — he would continue his practical laboratory work up to the age of 83. He also appears to have been a more humble and modest figure inclined towards integrity over renown.

Does that make him the better person? Hume would certainly like you to think so, and makes no attempt at objectivity. Béchamp is:

“…an excellent husband and father… his lectures were made delightful by his easy eloquence and perfect enunciation… his social manner possessed grace and courtliness.”

Pasteur received no such gratuitous character assessment. He was a “man of influence”, a gifted communicator and socialiser; someone who approached science less as an artist exploring nature’s secrets, as per Béchamp, but more for its “commercial” benefits; someone “never to have left an effort of his unrecorded”.

Even the compliments feel somewhat loaded, passive aggressive:

“Intense strength of will, acute worldly wisdom and unflagging ambition were to be the prominent traits of his character”.

This is Hume’s more generous summary of the two:

“Alert determination is the chief characteristic of Pasteur’s features; intellectual idealism of Béchamps.”

There is another angle we can take. Pasteur’s story is straight from Hollywood: suitably so, for someone who moved comfortably in high places.

Béchamp’s, on the other hand, was undoubtedly a human story, which more often than not necessitates tragedy (there’s a jagged black pill for you). A man dignified in his flaws; obsessed with work for which his efforts would never be fully recognized; clearly naive and idealistic in his belief in the purity of science. But, overall, a story characterized by immense suffering and sadness: not the least when he lost his gifted son and co-worker Joseph at the age of 44.

In fact, while far less worthy of Hollywood, The Pasteur Conspiracy is also The Béchamp Tragedy: the story of a brilliant man who would live to see his wife and four children die and his life’s work hijacked by the Germ Conspiracists.

The moral of the story may well in fact be that the naive and idealistic Béchamp was played by the more cunning and scrupulous Pasteur. And that, quite possibly, we have all been similarly played since.

When I originally started this exploration of the origins of The Coronaspiracy, I had a rough idea in mind: prove that Pasteur was an elite stooge, probably even the original Germ Conspiracist — perhaps even offering verifiable proof that he was a Freemason who ate babies in his spare time — and thus ideally also proving that Germ Theory was a nature-inverting satanic fraud right from the get go.

I searched through pretty much every photo of him on the internet, and not one contains a Freemasonic hand sign — disappointing, I know, but perhaps they were less blatant with the symbolism than our current crop of indiscreet elites. Well… except for this one:

They just can’t help themselves, can they.

Illuminated Mason or not, what we can conclusively say is less sexy but still incredibly important: Pasteur was a grifting scientific hack. He cut corners, he made assumptions, he stole — theories, ideas and undeserved credit. In other words: he would make a fitting member of our contemporary group of Germ Conspiracists-in-Chiefs, because it is the group that he founded.

Thus, perhaps it is fitting that the Pasteur Conspiracy is, at heart, as disappointing as the man himself: a tale of hubris and entitlement, moral scruples and political allegiances — but also, perhaps most importantly of all, a fundamental lack of curiosity and attention detail about the workings of the natural world.

So, while there will be more nefarious wombat holes to be delved deeper into The Coronaspiracy, The Pasteur Conspiracy provides the theoretical framework to understand just how the Germ Conspiracists managed to get away with as much as they have: because they know that when it comes down to the crunch, we would rather follow the story than the science.

Further proof that it might just all be a movie, after all.